Logical Fallacies: Logical fallacies can be an unpleasant surprise when you’re writing an essay, preparing for an English examination, or even arguing with someone face-to-face. Luckily, though, it’s not that hard to avoid them! If you know what to look out for and how to avoid these common mistakes, you’ll have no trouble demonstrating your mastery of the English language and unlocking your potential in any situation!

- Logical Fallacies Definition

- Types of Logical Fallacies

- Categorical Fallacies

- Verbal Fallacies

- Material Fallacies

- What is a logical fallacy?

- Where can I find logical fallacies?

- How many logical fallacies are there?

- What are the five major categories of fallacies?

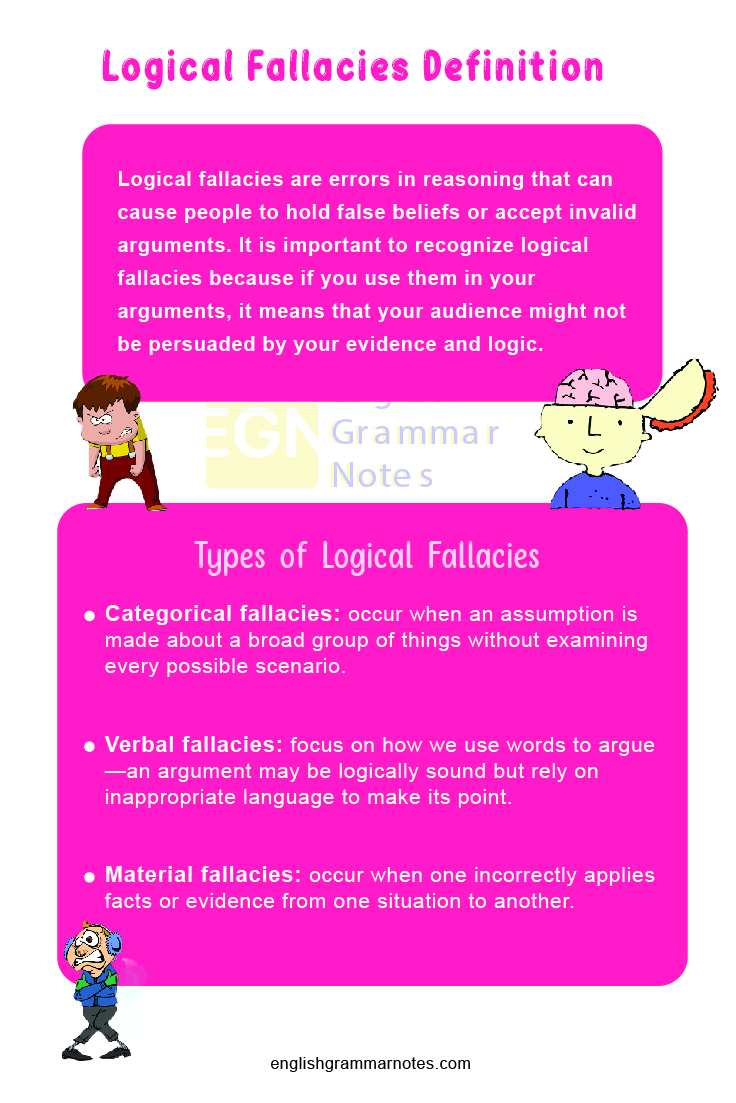

Logical Fallacies Definition

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that can cause people to hold false beliefs or accept invalid arguments. It is important to recognize logical fallacies because if you use them in your arguments, it means that your audience might not be persuaded by your evidence and logic.

Examples of logical fallacies ad hominem (or an argument against a person):

- An attack on a person’s character rather than their argument Circular reasoning

- Using an argument as support for itself Equivocation

- Using multiple meanings of a word interchangeably Hasty generalization

- Making sweeping claims based on insufficient evidence Straw man fallacy

- misrepresenting someone else’s position and then attacking it Understating complexity

- Oversimplifying complex situations Wishful thinking

- Holding one’s desires as facts

These logical fallacies examples are only a small subset of all possible logical fallacies. Learning What is a Logical Fallacy how to identify them will help you avoid making these common mistakes when communicating with others about politics, religion, or other controversial topics!

Types of Logical Fallacies

There are several classifications for logical fallacies, but in this article, we will learn about classifications based on the process by which they occur. There are three main types of logical fallacies:

- Categorical.

- Verbal

- Material

- Categorical fallacies occur when an assumption is made about a broad group of things without examining every possible scenario.

- Verbal fallacies focus on how we use words to argue—an argument may be logically sound but rely on inappropriate language to make its point.

- Material fallacies occur when one incorrectly applies facts or evidence from one situation to another.

Categorical, verbal, and material fallacies can all occur during an argument, so it’s important to be able to identify them when they happen. By learning about logical fallacies and how they work, you can ensure that your arguments are based on solid reasoning, not empty rhetoric.

Categorical Fallacies

The first group of fallacies is called categorical fallacies. These are mistakes in reasoning where there’s an error in how you set up your categories. You could either be using completely unrelated things as if they were related or similar things that aren’t similar enough to conclude they are.

- Categorical fallacies are kind of hard to explain, so let’s look at a few examples: Everyone who plays video games is short-sighted and doesn’t do well in school. Therefore, all people who play video games will have trouble reading books and won’t get good grades on their English tests. In other words, people who play video games must have bad eyesight and will never get good grades on their English tests because everyone who plays video games has bad eyesight and doesn’t do well in school.

- That’s a fallacious argument, but notice how in both cases there’s an error when it comes to setting up categories. In one case, we take two unrelated things and put them together as if they’re related. In another case, we have two things that are similar enough but not different enough for us to jump to conclusions about what will happen when we change one of them.

There are three basic types of categorical fallacies:

- Dichotomous

- False dilemmas,

- An either/or

Dichotomous: This happens when you set up a category with only two options (either A or B), even though other options can also be considered. For example, if someone says, “Either we accept their offer of $10,000 for our house or we burn it down and lose all of our possessions,” then they’re setting up a dichotomy where there are three options:

- We could accept their offer.

- We could burn it down.

- We could do neither and continue living in our house.

False dilemmas: This happens when you present a choice as to if it’s a dilemma, which it isn’t. For example, if someone says, “If you’re not with us, then you must be against us,” they’re setting up a false dilemma because there are other options available besides being for or against them. There are many more examples of false dilemmas in politics and current events. Either we go to war or everyone dies. We have to get rid of these terrorists or everyone will die.

An either/or: This happens when you present a choice as to whether it’s an either/or, but it isn’t. For example, if someone says, “You can’t be good at your job and have a family life,” then they’re setting up an either/or where there are three options:

- You can be good at your job.

- You can have a family life;

- You can do both.

This can be a tricky fallacy to recognize because, in some cases, it’s obvious that we’re dealing with a dichotomy or an either/or. However, there are also cases where these fallacies are hidden behind seemingly valid arguments.

Verbal Fallacies

A verbal fallacy is a mistake in reasoning that occurs when someone uses a word or phrase incorrectly. We all make these mistakes often, as they’re usually quite subtle—for example, equivocation and ambiguity. A good way to avoid these fallacies is to pay attention to how you use words in everyday speech. It can often trick people into believing something untrue or incomplete.

If you make a verbal fallacy in your everyday speech, it probably doesn’t reflect poorly on you. They’re usually pretty common mistakes. But if you use them in your work or everyday arguments and reasoning, it might be time to brush up on some common examples. For example, there are four main categories of verbal fallacies:

- Ambiguity

- Equivocation,

- The Argument for Ignorance

- Begging the question,

These are just a few examples of verbal fallacies. It’s not an exhaustive list, but it can help you think critically about your use of words and phrases. Just as your choice of words impacts how readers interpret what you write, so too does their use in everyday conversation. Recognizing these verbal fallacies can also improve your ability to spot them in others’ work and avoid committing them yourself.

Material Fallacies

A material fallacy is a type of logical fallacy that pertains to an argument’s content. They are based on misleading premises and thus fall under informal logic. By definition, these fallacies cause one to draw false conclusions about something and therefore should be avoided in both formal and informal settings.

- Examples of material fallacies include ad hominem arguments, hasty generalizations, and appeals to emotions or social norms as opposed to reason. In other words, these are logical errors that result from content faults, i.e., an error in what you’re saying rather than how you’re saying it.

- For example, when you argue that your opponent is wrong because he’s stupid (ad hominem), you’re committing a material fallacy; another classic example of a material fallacy is when you assert something is true because everyone believes it is (appeal to popularity).

- The most common way to avoid committing a material fallacy is to stick to propositions that are factual—provable statements that your audience can agree or disagree with, based on evidence.

- That said, each fallacious argument has its unique problem: we can’t always prove what’s true (for example, we don’t know for sure that God exists), but we should still stick to facts and stay away from claims based on appeals to emotions or social norms. You may have heard of some of these logical fallacies before, either in school or in popular culture.

Examples of common material fallacies Ad hominem – Latin for to/toward the man, an ad hominem argument is an argument that attempts to counter another argument by attacking its source instead of addressing its claims. For example, if you were to say My opponent is wrong because he doesn’t know what he’s talking about, you would be committing an ad hominem fallacy.

See More:

FAQs on Logical Fallacies PDF

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning that renders an argument invalid.

2. Where can I find logical fallacies?

You can find logical fallacies all over – they’re prevalent in political discourse, particularly during election season; on social media (and in other internet comment sections); and even in arguments with friends and family.

3. How many logical fallacies are there?

There is no definitive answer to how many logical fallacies exist, but it’s safe to say that there are several hundred. Some sources claim that over 500 have been identified, while others claim that there may be over 1,000. This is because a fallacy can be divided into numerous sorts of variations on a theme; for example, circular reasoning can be classified as either begging the question or post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

4. What are the five major categories of fallacies?

There are five main categories of fallacies, and they can be further divided into several different types: formal, informal, material, verbal, and equivocation. We’ll go over each one below.

Conclusion

We conclude our discussion of logical fallacies by stating that there are several general rules you can follow to avoid them. First, it’s important to keep in mind that any argument (or conclusion) is only as strong as its weakest link—if one of your premises is weak, then your entire argument will be weak.

Additionally, it’s wise to be aware of different logical fallacies; knowing what each fallacy looks like and understanding how they function will help you avoid committing them yourself. Finally, always try to look at arguments from both sides before concluding—this way, you’ll know if an argument is convincing or not. Good luck!