Hasty Generalization Fallacy Examples: A conclusion that is solely dependent on a hasty generalization must always advance from the specific to the broad and vague end. It primarily includes a small group and aims to infer a generalization about that random sample to a general community, but it fails miserably.

Hasty generalization examples in politics are pretty much ubiquitous and may usually be voiced throughout the campaign season. However, it is up to us and our rational intellect to figure out how to avoid hasty generalization.

Faulty generalization examples are always prominent in our everyday communications. In this article, you will discover further about them and how to potentially avoid them, in addition to making your arguments stand out.

Hasty Generalization Fallacy

- What is a fallacy?

- What are some common fallacies?

- What is Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

- What other terms do we have for the Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

- Some general illustrations of the Hasty Generalization Fallacy

- Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in Politics

- Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in Social Media

- Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in the Advertising Sector

- How to Overcome the Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

- To sum it all up

What is a fallacy?

The act of actively supporting an assertion with the assistance of related statements is termed as reasoning or argumentation. The conclusion is the assertion you’re trying to establish, and the premises are the claims designed to back up that claim. There are two types of reasoning: valid and flawed. When argumentation is managed wrong, it is alluded to as a fallacy.

A fallacy is a cognitive or reasoning blunder that culminates in an ideology based on irrational or deceptive assumptions. Fallacies are sometimes explicitly utilized to influence other people’s opinions, notably in marketing and impromptu discussion and debate.

Even though some fallacies are deliberate, it is basic to produce logical mistakes accidentally. Therefore, it is necessary to confirm one’s reasoning with the same thoroughness that one evaluates the views of others.

There are many diverse categories of fallacies, which are characterized according to the types of logical flaws they comprise. Some kinds incorporate generalizations, for instance, assuming a definitive conclusion from an inaccurate generalization or drawing conclusions as a rule of thumb from a specific instance.

To put it in other words, a fallacy is a logical and reasonable inaccuracy.

What are some common fallacies?

The Fallacy of Appeal to Authority

This kind of argument attempts to substantiate a claim by appealing to the individual presenting the argument.

The Fallacy of Popularity Appeal

Appeal to Popularity is a fallacy whereby someone expresses an opinion predicated on prevalent sentiment or a shared view among a set of individuals.

Ad Hominem Fallacy

Ad hominem arguments attempt to invalidate an opponent’s claim by directly attacking the person making the argument. This is generally known as a personal attack.

Hasty Generalization Fallacy

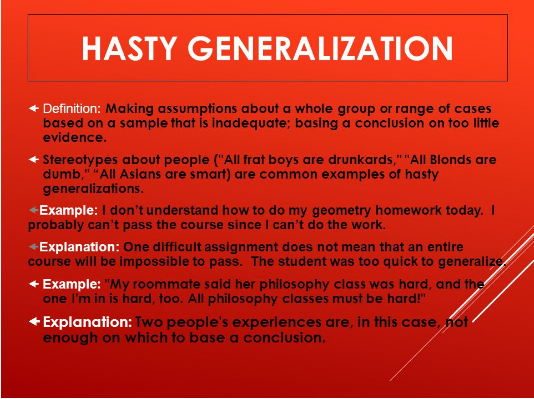

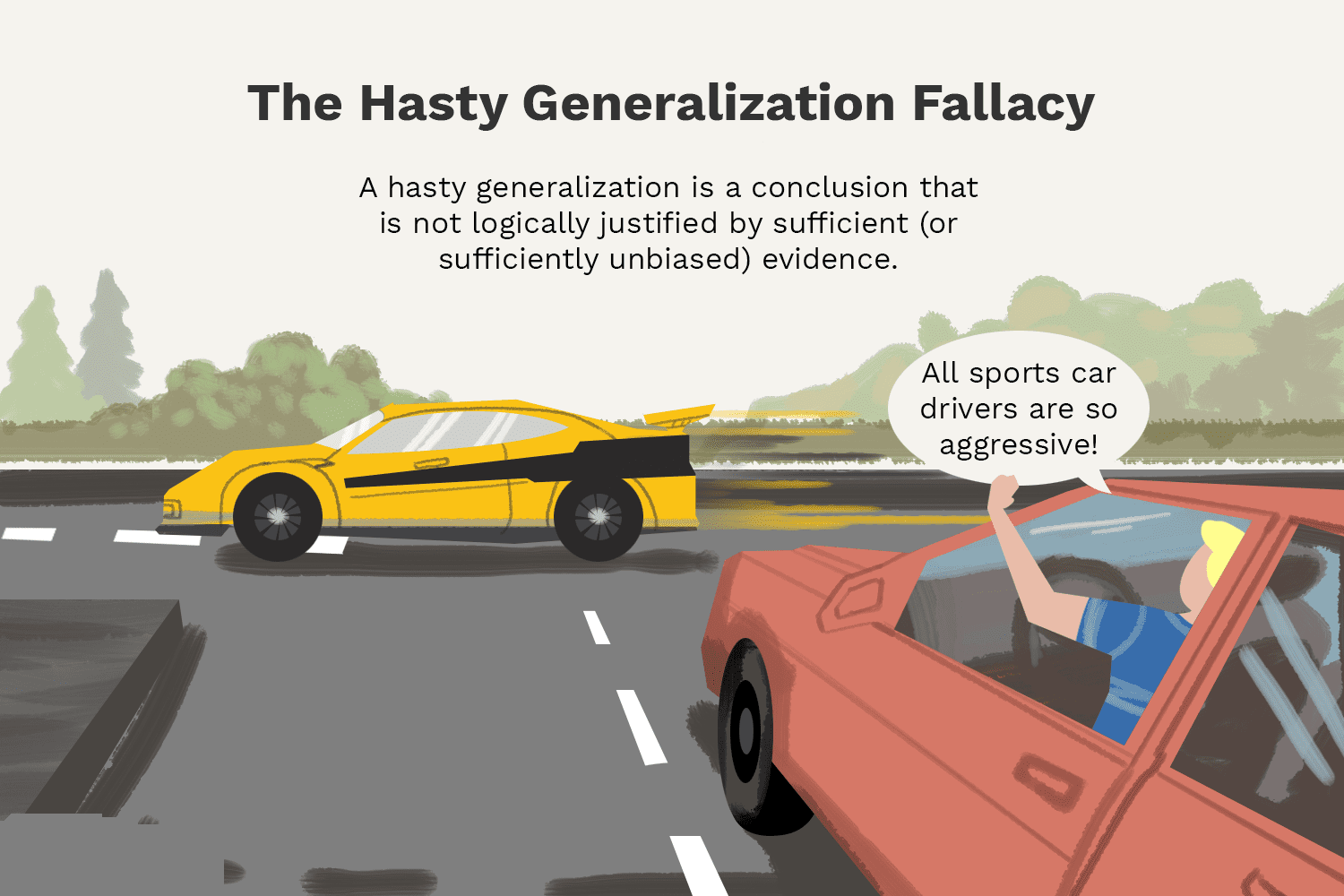

Vary according to the size of the very first sampling; a generalization is stronger or weaker. Generalizations made impulsively are inadequate generalizations.

When we support a general assertion before seeing a significant enough sample to be completely convinced that the statement is correct, we commit a hasty generalization.

· The Straw Man Fallacy

It is a logical fallacy in which anything (a person, a perspective, or an idea) is simply replaced with a twisted interpretation that exaggerates the opponent’s viewpoint to make it simpler to criticize openly.

What is Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

The over-generalization fallacy is yet another synonym for the hasty generalization fallacy. It’s essentially stating that it’s too modest drawing on statistics. In other words, you can’t bring a statement and assert that something must be completely true if you just have one or two cases to support that assertion.

This is also an illustration of rushing to judgment, the terminology used in psychology to describe judgments or evaluations made before all relevant information is available, culminating in an erroneous, false conclusion.

The following is an example of a hasty generalization:

- For B, A is appropriate.

- For C, A is appropriate.

As a consequence, A holds true for D, E, F, G, so on and so forth.

We’ve taken a verdict based on only two samples in this instance. However, what is relevant for the sample may not even be completely true for the majority of the population.

What other terms do we have for the Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

Hasty Generalization Fallacy can also be alluded to by the following terms:

- Argument by generalization

- Argument from small numbers

- Biased generalization

- Converse accident

- Faulty generalization

- Hasty induction

- Inductive generalization

- Insufficient sample

- Jumping to a conclusion

- Lonely fact fallacy

- Neglect of qualifications

- Overgeneralization

- Secundum quid

Some general illustrations of the Hasty Generalization Fallacy

Here is an example that we can all identify with:

Would Romeo and Juliet have been spared an awful death if they had just waited for one more minute? This is a question that persists even to this day.

The denouement of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is mandated by dramatic irony, but Romeo’s hasty generalization of Juliet’s death may have been benefitted from a little more proof before jumping to that final conclusion.

Here are a few more illustrations to better your understanding:

- I had a poor experience with certain merchandise on an online retailer’s website. And I immediately conclude that the website is completely untrustworthy and that all of the things for sale are substandard.

- My father and brothers never assisted me with household responsibilities when I was younger. In the household, all males are utterly worthless.

- She was once pickpocketed on a London street and concluded that the city was potentially unsafe.

- The class topper in Arush’s class was immensely proud of his personal accomplishments and unwilling to assist anybody. Arush arrived at the notion that all toppers must be similar.

- People turned down my requests when I asked for directions since they were inscribed in Spanish, so I notified my mother that the Spanish people were arrogant and unhelpful.

- Rohan was once bitten by his friend’s pet dog at home, and he still considers that all dogs are aggressive beasts.

- My child was harassed and bullied by his preschool peers. Bullies intimidate all of the children.

- His associate was a Harvard female who once messed up a trial’s documents, and he feels that women can’t do a job as good as their male counterparts.

- The fitness routine, according to anyone and everyone who participated in the questionnaire, helped them lose some weight. As a consequence, everyone who participated in the program lost weight.

- Riya’s previous relationship ended when her former lover was disloyal, and she’s reached a conclusion that men simply can not be trusted.

- Rahul’s grandparents had never used a smartphone. Kevin firmly believes that everyone over the age of 50 is technologically incompetent.

Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in Politics

Just one of many unforgettable quotations from Trump’s announcement of his candidacy was the following:

Mexico does not send its best of the best when it sends its people. They’re not planning to send you. They’re never going to send you. They’re actually sending individuals with a plethora of problems, and they’re carrying those structural issues with them to us.

They’re introducing drugs, serious crime, and rapists, and I presume some of them are nice people.

This is a case of hasty generalization. Trump thinks that the significant majority of Hispanics are criminals and rapists, drug smugglers, or generally criminals, regardless of the fact that he has no evidence to substantiate his grandiose claims.

He not only concludes that Mexico is actually bringing illegal immigrants across for a specific purpose, but he also concludes that they are hardened criminals without any data to back up his sweeping statements.

Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in Social Media

You’re undoubtedly constantly being bombarded with smiling faces of friends (and acquaintances) who actually look to be enjoying the perfect life as you browse through your social media feed.

People are seen at major events, out together with friends and family, and on lavish vacations with their wonderful families and friends in photo after photo.

And you immediately conclude that they are quite content with their life, which appears to be a bed of red roses without thinking twice. This is an example of hasty generalization fallacy, and today, and it has become very much evident in our fast-paced lives.

Your representative sample of their current living situation, on the other extreme, is minuscule–just one precise moment out of thousands.

This isn’t even relatively near to becoming reasonable evidence that someone else is joyful, completely free of troubles, and has everything they necessarily require in daily existence. Your friends’ beautifully constructed Instagram photos are extremely unlikely to be an honest depiction of their regular lifestyle.

Examples of Hasty Generalization Fallacy in the Advertising Sector

The most obvious example is advertisements that juxtapose before and after photographs of a specific individual who tried a certain product and achieved the intended outcomes.

Many consumers succumb to these tricks and buy the product without considering the complete context, only to be bitterly disappointed when they do not see the promised benefits.

What they don’t realize is that the sample size is so small, and yet they follow suit!

How to Overcome the Hasty Generalization Fallacy?

- Focusing on improving your capacity for critical thought is vital to combat the hasty generalization fallacy. In this instance, inaccurate cognition originates from the use of a dataset that is too insufficient to substantiate a comprehensive initial assertion.

- You should resist establishing sweeping statements based primarily on tiny samples if you really want to refrain from making hasty assumptions. Alternatively, reserve a conclusion on strong generalizations until you’ve accumulated enough proof to substantiate them.

- The evidence which supports a generalization should only be as robust as your conviction to it. Even if you have a significant sample size to justify a generalization, you must remain your allegiance to that generalization open to modification when new information becomes available.

- A high sample size, on the other extreme, does not simply ensure trustworthy results. To begin, double-check that the sample you’re using to generalize is fairly typical of the overall population.

This is where the study methodology enters the picture: examine the number of respondents or how the researchers interpret the survey.

Also, examine the piece of investigation you’re looking at. Specific incidents of anecdotal evidence might be inaccurate and misleading, so consider them with a healthy dose of scepticism when you stumble across them.

The fact of the matter is that we endeavour for the highest degree of credibility in all of our writings, including fiction and nonfiction.

Although it requires a bit more time and commitment, being cautious about the authenticity of your assertions can help you to establish a stronger voice and credibility with your readers.

To sum it all up

When we inappropriately generalize from a misrepresentative sample, we call it a hasty generalization. Many clichés are predicated on them.

Because of our inclination to compartmentalize and divide individuals into distinct social realms, everyone has implicit biases concerning people of different backgrounds.

Unconscious bias is significantly more frequent than explicit prejudices, and all these biases easily and frequently contravene one’s genuine principles. Stereotyping can be extremely devastating.

Hasty generalization fallacies lead to assertions like “Anita is a horrible driver; thus, all ladies are lousy drivers.” When making such comments, we must thoroughly examine all factors and ensure that our facts are correct.

Analyze, evaluate the facts and figures, and properly assess your primary source to avoid forming or blindly believing a hasty generalization. Search for signs that both confirms and directly contradicts a hypothesis and make your best evaluation from there to identify anything that is near to the truth of the matter.

If you don’t have enough insight, don’t jump to any conclusions. Our confirmation bias sets in once we draw a hasty generalization, cementing our ideas with each and every incident we eventually meet. And, absolutely, we should not stereotype a whole group based on a solitary incident that happened.